1. A boy convinced of his guilt regarding a crime he cannot remember wanders into a city. He has a piece of paper with a name that he doesn't recognise on it.

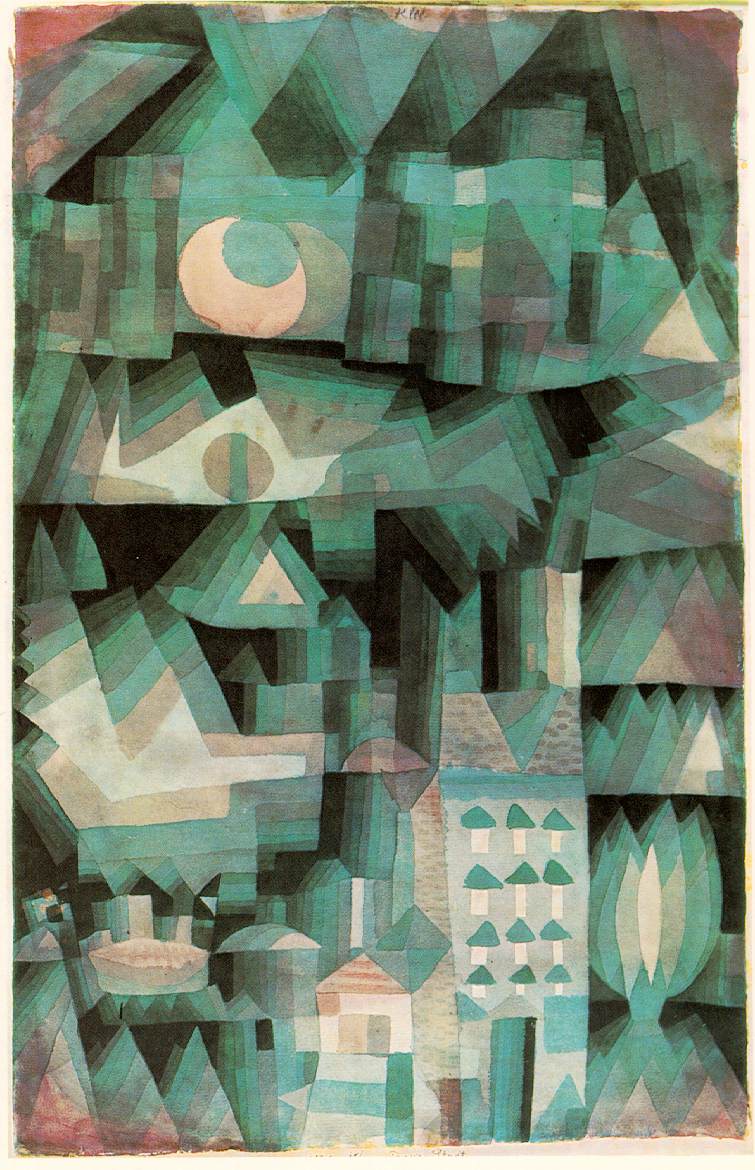

When science fiction bleeds into dream, it is elusive and unsurpassable. Fictional worlds are churches for poisonous spiel and necessary imaginings alike; place maps for a multi-dimensional drift, place maps that do not display possible routes so much as possible versions. Hans Wilmots' Die Stadt, La Ville, The City stands as an attempt to erect a dreamworld in celluloid like no other: Stunning psychogeographies are inspected and offered, but never crystalised, for our protagonist, The Boy (Victor Grueber) is somewhere between knowing where he is and not knowing where he isn't. Wilmots, an obsessive fan of pulp sci-fi and experimental fare alike, sought to '...bring a hopeful confusion to the die-cast certainties of space-age cinema'.*1

2. The boy shows the name on the paper to various people he meets. Each shifts uncomfortably, unwilling to help.

So when Delany's Dhalgren runs a red light and collides with Calvino's Invisible Cities, creating a lightning bolt impact that throws both from the left-to-right 2-d page to the back-and-forth 2-d screen, we get something new; a bold attempt to transmit palpable shock of life in a dream city.

3. Eventually, a man gives him directions to a an apartment. When he gets there, he recognises the apartment as his own.

The city, which appears as a shifting diorama, an ever-changing series of urban desserts and oases, dragging at his memories and desires. Look, a beautiful girl, weeping, running down an alley, who, when followed, skips into a laughing dance and suddenly we are on a bridge, high over the metropolis' permanent buzz. The city at various points appears to be an amalgam of Medieval Venice, Berlin during wartime, Pinocchio's Pleasure Island, a future-Paris. As the boy wanders, looking for 'some truth' (as he keeps saying, with increasing panic) it shifts.

4. He opens the door. Inside, is a man sitting at a table. It is himself, in the future. It is his father, from the past. It is a complete stranger.

The boy's search has the nonsense quality of The Trial or Alice In Wonderland, as red herrings and hot leads are interchangeable. Given directions north to terracotta slums, he instead finds a golden palace; sent south to speak to a man in a tavern, he finds his way obscured by a carnival celebrating the completion of a hundred metre high fish tank. The city bends to avoid his query. The locals speak in a hybrid tongue, sometimes German, English, French or Wilmots' native Flemish. Sometimes subtitles aid us, sometimes they are absent. Other times, they seem to lie. Misty camerawork tricks us further.

5. 'I've been here before. This is my city' the boy says.

'It had the same name, but it was a different city. That city is dead, one thousand times over. We sell postcards to allow you to remember it's demise,' says the stranger.

'Why do I feel guilty?' says the boy.

'Humanity's default position is guilt, my boy. You're lucky you have a sole act to pin it on. you're luckier yet to have forgotten it' says the stranger.

'I wanted to make something hot and vague' said the director. When Hollywood came calling to remake the film, Wilmots suggested that they make one hundred remakes, all with slightly different journeys and endings, to negate the 'natural closure demanded by the optimistic American mind.'*1 To this day, no-one has tried.

Die Stadt, La Ville, The City Directed by Hans Wilmots Written by Hans Wilmots, Franz Franz, Starring Hector Grueber, Dmitri La Salle, Agnes Scifo Criterion Pictures/ Belgique Cinema Release Date UK: May 1986 US: January 1988 Tagline: 'Where is the City?'

*1. FilmMonth interview, Spring 1996.