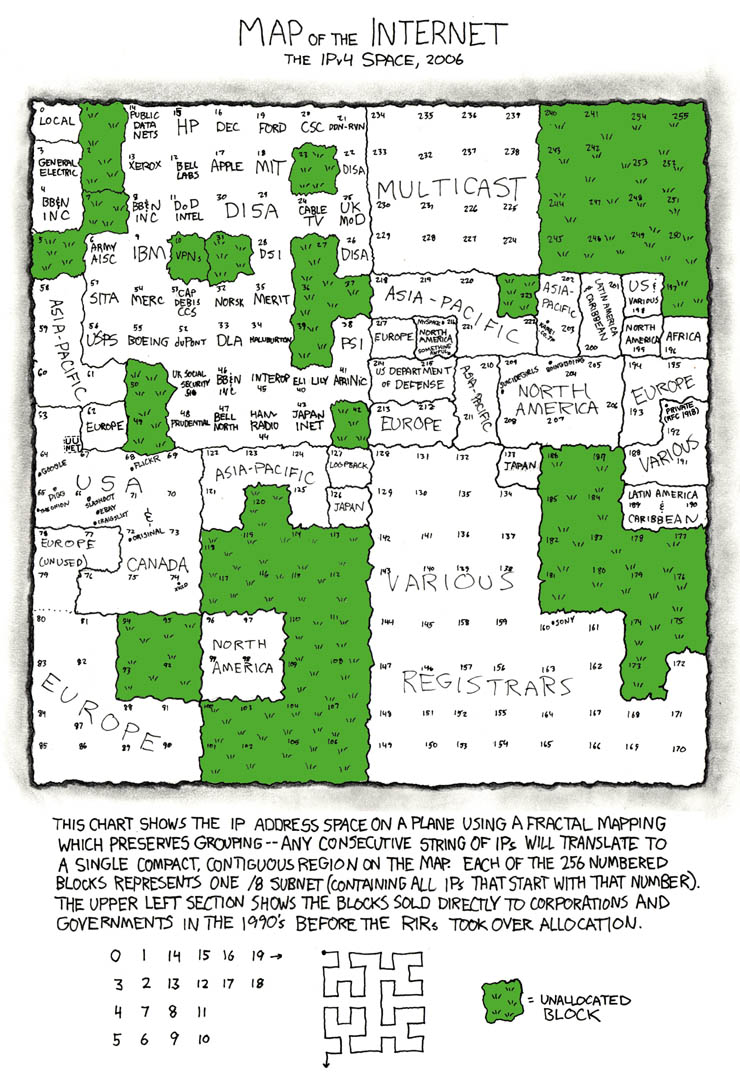

It is a film about repetition. I'll say that again; it is a film about repetition and originality; about how two things can never be identical. Mark aims to discover whether he is the truer original than the other blogger, but finds his every move countered by the nefarious idea-xeroxer. For plot reasons best left unexplained (because, truthfully, they are not apparent) Mark goes into the internet with the help of a neurotic science student (Kirsten Dunst). The movie then becomes a meta-fictional Tron, a graphic hell of neon id fancy. Mark discovers that from the inside, the internet is a live electric forest, and is run by The Sage (Judi Dench) who is concerned by the pollutants filling up the wiry treelungs with 'content'. The Sage speaks only in dialogue that is a patchwork of quotes from others, as this monologue shows:

'Heathcliff! It's me, I'm Carefree! 1 LOL!2. You humans just ride along the information superhighway, wind down your virtual windows and litter comments along the verges. Your regard for the unnatural world speaks poorly for the sake of your souls.'3

Mark is moved by such a forceful plea. As a prime contributor of such effluence, Mark struggles to justify his existence, and the existence of his race. 'When I was a child, I dreamed of such technology; who would have forseen that I would use it to write rubbish and contact schoolfriends who do not remember me?'

Wilson's portrayal of Mark as the grinning but melancholy everyman is predictably sound and allows for Gondry to raid the cupboard marked Existential Pyrotechnics (fourth drawer down, below Post-postmodernism and Ironic Post-mortems). But it is Mark's quest for truth, beauty and heart in the inner workings of the internet that allows the movie to work. He is struck by The Sage's final quote (uttered as she is slain by The Space, a violet void that sucks her up and away):

'We await the day with relish that somebody dares to make a dance record that consists of nothing more than an electronically programmed bass drum beat that continues playing 4/4 monotonously for eight minutes. Then, when somebody else brings one out using exactly the same bass drum sound and at the same beats per minute, we will all be able to tell which is the best, which inspires the dance floor to fill the fastest, which has the most sex and the most soul. There is no doubt, one will be better than the other'4

He repels the monster with it's glorious informations, and goes on to throw himself into the eye of The Space, whereby he meets his dream and nightmare: A statistical print-out of everything he has ever done, on one long stretch of paper. He discovers that there is no other blogger copying him, merely a virtual mirror that confronts him with his own thoughts before he thinks them. Thus he comes to see the internet as a massive haemorrhage of sub-Freudian lust and fancies. He is horrified to discover how much time he has wasted with pointlessness like working and getting things done, and he vows to sleep and eat much much more when he re-enters the real world...

...and at that he does return; his lesson, whatever it was, learned, his white rabbit hunted down and interrogated. There is time for a love scene and amoral (sic), before the Flaming Lips tune specially penned for the movie, Desktop of My Heart, chimes in in all it's predictable wobbly indie loveliness, and there isn't a dry vest in the art-house.

Fictional Film Club Directed by Michel Gondry Prduced by Anthony Bregman Written by Michel Gondry and Marc Savidge Starring Owen Wilson, Kirsten Dunst, Judi Dench Music by Wayne Coyne Focus Pictures Release Date UK/US: April 2010 Running Time: 103 mins Tagline: 'Is Nothing Pointless?'

1. The first line the sage utters is actually a misheard lyric, another Gondry dig at the misinformation abounding in cyberspace. The line is from Kate Bush's Wuthering Heights, and should of course read as 'Heathcliff, It's me I'm Kathleen'

2. LOL: The earliest use of this popular internet shorthand meaning 'Laughing Out Loud' has been attributed to Ernest Hemingway, in his novel For Whom The Bell Tolls when an American soldier over a radio replies to an officer's order to mount a suicidal counter-offensive by saying 'Lima Oscar Lima, sir, the men sure think that's funny at this hour.' The exclamation 'WTF' meaning 'What The Fuck' is also used in the same conversation, when the radio operator is informed that he will be shot as a coward. As he is about to respond, artillery fire hits his position. 'Whisky Tango Foxtrot, sir! We're buried!' he shouts. This was not the first time the WTF shorthand was described in print however, and some attribute the first use to be as far back as John Bunyan in his Pilgrim's Progress, but this citation is disputed. 3. This is a direct lift from H.G Wells' Prince Kompooter, published in 1897 and believed to be the first modern reference to the internet.

4.Here the sage quotes from The Manual: How To Have A Number One The Easy Way by Jimmy Cauty and Bill Drummond, otherwise known as the Kopyright Liberation Foundation, or KLF.

5 footnote; disambiguation. See 6

6 see 7

6 see 7

7. see 888

8. This footnote scene is a note-perfect pastiche of a scene in exploitation kung-fu action flick Crazy Office Kickbox (Dan Ten, 1972) in which the hero must summon the ninja might of ten limbs to defeat the haunted photocopied, collated and stapled demons at work. Gondry uses exactly the same dialogue in the Fictional Film Club scene as in Crazy Office Kickbox, creating a dual echoing narrative that drives minds round bends.9

888. These quotes include oft-repeated witticisms from Twain,Wilde and Churchill and wise sayings from King and Mandela that Mark has received so many times attached to emails as to have been relegated from 'great' in his mind to 'downright lethal', causing his digitised brain cells to almost overheat in insipid pointlessness.

9. Gondry does a similar thing later in the movie, substituting dialogue from the climactic love scene between Mark and the neurotic science student and replacing it with speech from Aristocats (Wolfgang Reitherman, 1970) and Robocop 3 (Fred Dekker, 1993). This reinforces The Sage's argument that the world is drowning in all manner of trivial pop ephemera. The romance is hidden behind irony, the irony behind trash. But Wilson and Dunst smile, and we are saved.

888. zzk LOL. goto line 10

10 If > go to 20

20 If <>